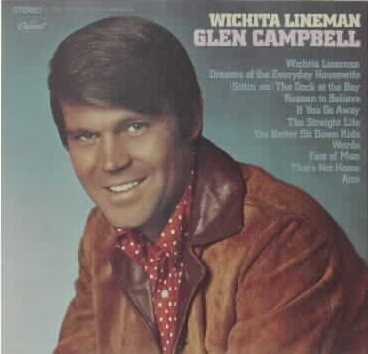

- Wichita Lineman

- (Sittin' On) The Dock Of The Bay

- If You Go Away

- Ann

- Words

- Fate Of Man

- Dreams Of The Everyday Housewife

- The Straight Life

- Reason To Believe

- You Better Sit Down Kids

- That's Not Home

Glen Campbell -

guitar, vocals

Jimmy Webb -

keyboards

Carol Kaye -

bass

Donald Bagley -

bass

James Burton -

guitar

Alvin Casey -

guitar

James Gordon -

drums

PRODUCER:

Al De Lory

"Wichita Lineman" is a popular song written by Jimmy Webb in 1968, first recorded by Glen Campbell and widely covered since. Campbell's version, which appeared on his 1968 eponymously titled album Wichita Lineman, reached #3 on the US charts, remaining in the Top 100 for 15 weeks. In 2004, Rolling Stone magazine's list of the "500 Greatest Songs of All Time" ranked "Wichita Lineman" at #192. It has been referred to as 'the first existential country song'.

Webb was inspired to write the lyrics when he saw a solitary lineman near the Kansas-Oklahoma border, possibly in Wichita County, Kansas or south of Wichita, Kansas. (Despite the identical names, the city, located in Sedgwick County, and county, which is in far western Kansas, are over 250 road miles (400 km) apart, and the city is noticeably closer to the Oklahoma border than the county. Campbell may have been referring to Sumner County, which is where Interstate 35 crosses from Oklahoma into Kansas.) Others believe that Webb had entitled the song "Ouachita Lineman," but that Campbell later changed that title to its present form. The lyric describes the longing that a lonely telephone lineman feels for an absent lover who he imagines he can hear "singing in the wire" that he is working on.

"Wichita Lineman" has been recorded by a diverse range of artists; from Ray Charles, Sammy Davis, Jr. and Dwight Yoakam to Kool and the Gang and Urge Overkill.

(excerpt from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wichita_Lineman )

Arrangement by Al De Lory:

In the first recording, by Glen Campbell, a notable feature of Al de Lory's orchestral arrangement is that the violins and a Gulbransen Synthesizer mimic the sounds that a lineman might hear when attaching a telephone earpiece to a long stretch of raw telephone or telegraph line i.e. without typical line equalisation and filtering. One would be aware of high-frequency tones fading in and out, caused by the accidental rectification (the rusty bolt effect) of heterodynes between many radio stations (the violins play this sound); and occasional snatches of Morse Code from radio amateurs or utility stations (this is heard after the line of lyric, "is still on the line"). Heterodynes are also referenced in the lyric, "I can hear you through the whine".

(excerpt from: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wichita_Lineman )

Wichita

Lineman:

Wichita

Lineman:

Wichita

Lineman:

Wichita

Lineman:

Wichita

Lineman:

Wichita

Lineman:

Wichita

Lineman:

Wichita

Lineman:

Wichita

Lineman:

The Greatest Songs Ever! Wichita Lineman

Songwriter Jimmy Webb was driving around rural Oklahoma when, in the middle of nowhere, he saw a lineman working on a telephone pole. Which gave him an idea for a song . . .

by Johnny Black

Blender, Oct/Nov 2001

As “Wichita Lineman” was being shipped, Lyndon Johnson was ordering an end to American bombing in Vietnam, and, shortly after, Richard Nixon would replace LBJ in the White House. Jimi Hendrix was featured in Look magazine, Cream were earning platinum records and the Bosstown Sound hype was flooding the media. The first 747 took to the air, the Apollo 8 astronauts orbited the moon and NASA selected the crew for the first lunar landing.

It hardly seemed an auspicious moment to release an old-fashioned homesick country ballad, but Glen Campbell and producer Al De Lory had booked sessions in Capitol Records’ Studio A in Los Angeles, and they were short of material.

“Glen and I had previously hit with ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix,’ ” recalls the song’s composer, Jimmy Webb. “I was living in Hollywood, in the former Philippine embassy, with 50 of my closest friends — a bunch of people hanging out. I paid the bills. I had a green baby grand piano. I got a call one day from Glen saying, ‘We’re recording; do you think you could write us another ‘By the Time I Get to Phoenix’?”

Despite his reservations about simply copying an earlier hit, Webb felt he could craft something with a geographical reference in the title, in a style similar to that of “Phoenix.”

“Some time earlier,” he says, “I had been driving around northern Oklahoma, an area that’s real flat and remote — almost surreal in its boundless horizons and infinite distances. I’d seen a lineman up on a telephone pole, talking on the phone. It was such a curiosity to see a human being perched up there in those surroundings.”

The image returned to Webb, and he spent two hours that afternoon “noodling on the green baby” until he came up with a tune. “Except that it wasn’t finished. There was a whole section in the middle that I didn’t have words for, which eventually became the instrumental part.”

What Webb didn’t know was that De Lory’s uncle was a lineman in Kern County, California. “So as soon as I heard that opening line,” De Lory recalls, “I could visualize my uncle up a pole in the middle of nowhere. I loved the song right away, and I knew it was right for Glen.”

Overruling Webb’s insistence that “Lineman” wasn’t finished, De Lory asked for a demo, which Webb recorded by simply placing a tape recorder on top of his piano.

Campbell familiarized himself with the demo, and within two days he was laying down the basic track in Studio A with his old colleagues from L.A.’s finest session team, the Wrecking Crew. “Carol Kaye was on bass, and she gave us the opening lick,” he recalls. “Then I used her bass, a Danelectro, to play the guitar solo.”

They cut the track in less than 90 minutes. De Lory took it home to work out an orchestral arrangement.

Meanwhile, Campbell dropped by Webb’s house, where he had a revelation. “Synthesizers were very rare in those days,” Webb says, “so I’d buy elaborate church organs with lots of stagey effects. I had a Gulbranson, which had a humming, resonating, reverberating electronic sound with a tremolo quality, but also an echo, so there was a lot of sustain. Kind of a bubbling noise.”

Webb demonstrated the sound to Campbell, suggesting that it might be good for evoking the sound of signals in telephone wires. “I loved it right off,” says Campbell, “so I ordered a company to come and dismantle this huge organ and move it to Studio A.”

Webb followed the organ to the studio and, on arrival, heard De Lory’s orchestration, including the signature Morse code-style violin stabs on the chorus of the song. “I was just the tiniest bit irritated that Al hadn’t asked me to do the strings,” he says, “because I was crazy about playing with orchestras. But Al’s arrangement was wonderful. I wouldn’t add anything to it or take anything away.”

Within 20 minutes, Webb added his Gulbranson sound. “Just three notes, but it produced a kind of electronic chiming — which might be a telecommunications sound, a satellite sound or something of that nature,” Webb says.

The sound appears as the track fades (at 2:44), and De Lory later doubled some of the keyboard with strings — the perfect finishing touch.

By December 21, 1968, “Wichita Lineman” had reached number 1 on the country singles chart, selling more than 700,000 copies in two months. On January 11, 1969, it hit its Billboard chart peak of number 3, and on January 22 the Recording Industry Association of America certified the song as gold.

Two months later, at the eleventh annual Grammy Awards, “Wichita Lineman” earned a Best Engineered Recording nod for the efforts of engineers Joe Polito and Hugh Davies.

“Every element in the track was perfect,” Campbell says. “It’s certainly the song that put me on the map.”

“It’s a beautiful, sad, yet not depressing piece of music,” says Mike Mills of R.E.M., who occasionally perform the song live. “It’s one of the most evocative songs I’ve ever heard.”

Webb feels the same way. “People say my songs and Glen’s voice were a perfect combination. He brought my music into the mainstream, placed it squarely in front of the public. My life would have turned out a whole lot differently if he hadn’t.”

(excerpt from: http://www.blender.com/guide/articles.aspx?id=194