(Roger Graham - Spencer Williams)

(Haven Gillispie - Arthur Sizemore)

|

|

|

|

| artist: | EMMETT MILLER AND HIS GEORGIA CRACKERS |

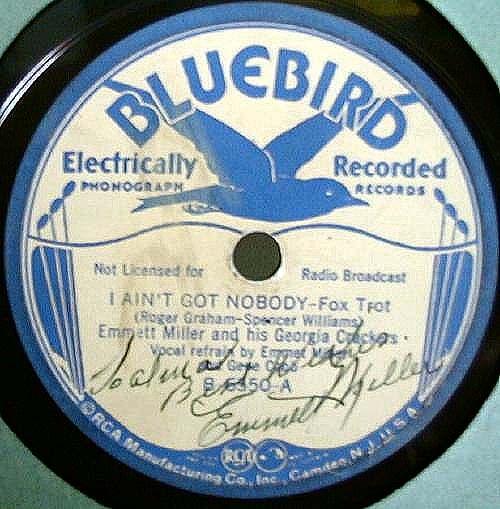

| label: | BLUEBIRD B-6550 |

| release: | 1928, USA, 10" 78rpm |

| A-side: | I Ain't Got Nobody (Roger Graham - Spencer Williams) |

| B-side: | Right Or Wrong (Haven Gillispie - Arthur Sizemore) |

| comment: | A-side is signed by Emmett Miller. |

Emmett Miller: Country Music’s Most Mysterious But Influential Missing Link "I would like to think that the world has heart enough to remember Emmett Miller as a catalyst for the music that came after him and before him..." - Leon Redbone "...here was a man, largely unknown to most modern day musicians and singers, who was one of the original architects of modern country and popular music..." - Ray Benson, Asleep At The Wheel "Without a doubt my father learned "Lovesick Blues" somehow from Emmett Miller. It was either by record or he heard him perform it in person at a minstrel show." - Hank Williams Jr. "Emmett Miller is one of the most intriguing and profoundly important men in the history of country music." - Nick Tosches, Author Emmett Miller’s sound can be heard in the works of Jimmie Rodgers. Milton Brown was a devotee of Miller’s music. A young musician named Bob Wills once declared Miller to be his favorite singer. Hank Williams covered Miller’s version of "Lovesick Blues" in 1949. Merle Haggard claims Emmett Miller as an influence, and dedicated part of his album, I Love Dixie Blues, to covering several Miller recordings. These are some legendary names in country music, and this man, Emmett Miller, seems to have been a major influence on both them and country music, yet has remained a virtual unknown himself. Emmett Miller may have remained a little known footnote in county music history, had it not been for author Nick Tosches first stumbling upon him, first through Merle Haggard’s album, and later, through a few sketchy references to him while he was researching his book Country (originally published in 1977). Those few elusive references to the mysterious Emmett Miller piqued Mr. Tosches curiosity as to his connection and possible influence on what would evolve, years later, into country music. At the time Mr. Tosches unearthed Miller, outside of a few extremely rare recordings, virtually nothing was known about him. Not even basic information as to when he was born, where he came from, where he went, or whether he was deceased or still living. There wasn’t so much as a photograph to be found, and no one knew for sure if Emmett Miller was even his real name. Outside of a few recordings, his life was based on speculation, including the year and place of his birth, which was thought by some to be 1903 in Macon, Georgia. It wasn’t until 1996, when the records of Emmett Miller’s death were finally stumbled upon, that any definitive facts regarding Miller were uncovered. The record of Emmett Miller’s death showed he died of carcinoma of the esophagus, on March 29, 1962 at the age of 62. Through obituaries and undertaker’s records, his grave site was found at Fort Hill Cemetery in East Macon, where he is buried along side of his parents. And from his headstone, at last, Emmett Miller’s birth date was found, February 2, 1900, and he was indeed born in Macon, Georgia. From that information, this much is known about Emmett Miller. He was one of five children born to John Pink Miller and Lena Christian, though only Emmett and a younger sister born in 1903, Nora Belle survived. Emmett’s parents were both educated, and saw to it their son was. He attended school through the 7th grade, with dreams of one day becoming a comedian. As a child he loved the Minstrel shows, and his great desire was to become a black-face performer in Minstrel shows. However in the meantime, before embarking on his dream, he worked for a time with the Central of Georgia, and he was listed in Georgia state records of 1917, 1918 and 1920 as being a chauffeur, boarding at the home of his parents. While he came of age nine months before the end of WWI, it appears that he was never called to serve. He married once, a short lived marriage to Bernice Calhoun on September 24, 1943, which produced no children. Those are the known of the facts of Emmett Miller, everything else that falls between his birth and death, has been pieced together through old newspaper and Billboard advertisements and articles, old record label catalogs, interviews with people who had known or worked with him, but who’s memories are greatly faded, and a lot of ‘connect-the-dot’ speculation. It’s widely believed that he started his professional career in 1919, and Emmett had left home by the age of 20. Miller’s whereabouts are largely unknown between 1919 and 1924, though it was believed he did stints with the Neil O’Brien Minstrels and the Dan Fitch Minstrels. The first real glimpse that Miller was fulfilling his childhood dream comes from a "Minstrelsy" column in an August, 1924 issue of Billboard reviewing the Dan Fitch Minstrels show that had played a three day engagement in Poughkeepsie, NY, with a mention of Miller in the show’s cast. The first concrete grasp on Emmett Miller and his career surface in the late fall of the year 1924, with his first recordings on the OKeh label. Those songs were "Anytime," which was his signature song on stage, and a cover of a 1918 song called "Pickaninnies Paradise." These recordings showed Emmett to be one of the strangest, yet most stunning stylists to come along up to that point. His voice was described as "otherworldly" and as the man with the "trick" voice. His music was a strange stew, his voice was country, but being a blackface performer, his vocals also encompassed the exaggerated "negro" sound used by blackface performers, and the arrangements of the music were based in jazz. By this time, scat singing had become the rage in jazz music, but Emmett shunned that and chose to yodel. Yodeling had already been commonplace in songs for quite some time by then, however, it was the standard European style of yodeling, done between words and lyrics. Particularly on "Anytime," Emmett yodeled, but it was a yodel unlike anything anyone had ever heard before. Emmett’s yodel was more of a guttural cry, an anguished release, and he used it while singing his words, as in one lyric that went "Now ain’t that nii-yii-yii-yii-yice." In the summer of 1925, Emmett emerged in Asheville, North Carolina, which was a resort town for the well-to-do, and known for it’s many theaters and music scene. It was a regular stop for Minstrel shows, as blackface performers were a favorite among the Ashville crowd. There were full page advertisements for Emmett Miller’s performances in the newspapers, heralding him as "OKeh Record Star" and "Asheville’s Favorite Blues Singer." That summer, Ralph Peer, then director of production for Okeh, decided to record his next batch of field recordings in Asheville, and checked into the George Vanderbilt Hotel and set up shop. During his stay, several performers were recorded, among them, Emmett Miller. He recorded four songs, "You’re Just The Girl For Me," "Big Bad Bill (Is Sweet William Now)," "Lovesick Blues," and "I Never Had The Blues (Until I Left Old Dixieland)." "Lovesick Blues" was written by Irving Mills and copyrighted in 1922. The song had been recorded several times before, however, it’s Emmett Miller’s 1925 version that gave the song it’s immortality. He was accompanied by a lone pianist, with his ‘trick voice" employing startling falsetto flights mid-word, his use of swooning pitch, eccentric timing and bizarre phrasing. This vocal style was present in his 1924 recordings and were used on all but one of the songs Emmett recorded during this session. These trademark sounds are an influence that can be heard in work of Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills, among others. Which leads to the speculation between an Emmett Miller-Jimmie Rodgers connection. While it is known that Emmett Miller was in Asheville in the summer of 1925, Jimmie Rodgers didn’t move there until 1927. However, according to the recollections of Turk McBee, who was an associate of Emmett’s, he places Jimmie Rodgers in Asheville at that same time, and claimed that Rodgers had auditioned for Ralph Peer and was turned down. Unfortunately, by the time Mr. McBee was located and interviewed, he was an old man with faded memories. His recollections haven’t been able to be substantiated so far, but they are intriguing possibilities that are feasible. Though Jimmie didn’t move to Asheville until 1927, it is quite possible he made visits before actually moving there. The fact that Jimmie did some work as a blackface performer prior to his seminal 1927 Bristol recordings makes that possibility even stronger. Since Asheville was one of the hottest spots in the country for Minstrel shows, it was a regular stop on the circuit, and if he were appearing with one of these troupes at the time, would have surely made appearances there. The possibility exists, that perhaps Jimmie saw Emmett perform then, and they may have even met, but there’s no evidence to support it as fact. Another strong possibility of their paths having crossed comes two years later, which places Emmett back in Asheville in June of 1927, at the same time Jimmie Rodgers was then living there. During this time, Jimmie had a short lived radio program (lasting two weeks), and there’s been conjecture that given Emmett’s popularity as a performer in Asheville, Jimmie would have wanted him as a guest on his show. Another intriguing theory is that it is known that Emmett Miller had a performance at the Majestic on June 6th, the same evening Jimmie was supposed to have had a broadcast. However, there was no Jimmie Rodgers broadcast that night, and the possibility has been raised that Emmett may have been a guest on Jimmie’s show the week before, and on the night of the 6th, he was at the Majestic performing with Emmett. By the end of the month both men had left Asheville, with Emmett heading to NY, while Jimmie went to Washington DC, before heading to Bristol in August, to record is first songs for Ralph Peer, who had by then had moved to the Victor label. Any contact between Emmett Miller and Jimmie Rodgers is all conjecture, but when looking at Jimmie Rodgers’ work it does give one pause to wonder. Those first sides recorded by Jimmie in Bristol two months after both men were in Asheville, contained yodels, but they were of the classic ilk. It wasn’t until his next sessions early the following year, that Jimmie recorded the first of what became known as his "Blue Yodels,’ which echoed the same distinctive style of yodel that Emmett Miller’s ‘trick voice’ produced. The opportunities for crossed paths between the two men, and the question of whether Emmett Miller was indeed a direct influence on the music of Jimmie Rodgers does raise some very interesting possibilities. In early June of 1928, Emmett entered the studio again to begin recording another 7 sessions, which would stand as his finest work. On most of these songs he was accompanied by a band that included Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, guitarist Eddie Lang and drummer Gene Krupa, who would all go on later to become jazz legends. The songs were released as "Emmett Miller & The Georgia Crackers." The songs recorded during the first session were "God River Blues," "I Ain’t Got Nobody," a remake of "Lovesick Blues" and a blackface dialog routine called "The Lion Tamer." Many versions of "I Ain’t Got Nobody" had been recorded by other singers prior to Emmett’s version, however, his version transcended all others, until Louis Prima combined the song with "Just A Gigolo" decades later in 1956. Emmett’s version became a favorite of Milton Brown, who took to performing it with his band The Light Crust Doughboys. When Milton left the band, Tommy Duncan was hired to take his place, and Bob Wills (then a member of the Doughboys) asked Tommy to sing it. Tommy laid Emmett’s version on him, and in 1935, they recorded the song with Tommy duplicating Emmett’s vocals as closely as possible. This second 1928 version of "Lovesick Blues," along with a version done by Rex Griffin in 1939 on Decca, which was a stripped down version of Emmett’s, were what Hank Williams based his own 1949 hit version on. Wesley Rose (Fred Rose’s son) had remembered Hank mentioning Emmett’s and Rex’s versions of the song, and asked Hank to send him copies of both recordings. When Hank cut the record, aside from a few lyrical changes, he replicated Emmett’s vocal styling with Rex’s more stripped down arrangement. The next set of sessions Emmett recorded in August of that year, produced a remake of "Anytime" and "St. Louis Blues." The following sessions recorded in September, spawned "Take Your To-Morrow" and "Dusky Stevedore." The 4th sessions were recorded in early January of 1929. The songs recorded at this session were "I Ain’t Gonna Give Nobody None O’ This Jelly Roll," "(I’ve Got A Woman Crazy For Me) She’s Funny That Way," and a blackface routine "You Loose." "Jelly Roll" was later recorded in 1937 by Cliff Bruner’s (a Milton Brown alumni) Texas Wanderers, and in 1951 by Jimmie Davis. By the time the next sessions were recorded in late January, the musical landscape was shifting. Emmett recorded three songs during this session, "Right Or Wrong," "That’s The Good Old Sunny South" and "You’re The Cream In My Coffee." These three songs were uncharacteristic of Emmett’s usual style. Where you’d expect Emmett to have let his "trick voice" go on "Right Or Wrong," his vocals were restrained. The latter two songs were done in a straightforward fashion that almost approached sincerity, but were lifeless. The popular new sound that was emerging was the "crooner" sound, being done by artists like Gene Austin, Rudy Vallee and Bing Crosby. It’s thought that this was the record label’s attempt at getting Emmett to tone things down to fit in among this new sound. "Right Or Wrong" though, became a favorite of Milton Brown who regularly performed it, and after he and Bob Wills parted ways, both kept the song in their repertoires. The 6th and 7th sessions were recorded in September of 1929, and produced the songs, "Lovin’ Sam (The Sheik Of Alabam)," a remake of "Big Bad Bill (Is Sweet William Now)," "The Ghost Of St. Louis Blues," Sweet Mama (Papa’s Getting Mad)," and "The Blues Singer (From Alabam)." Though he appeared on OKeh’s 3 record release of Atlanta’s Fiddler’s Convention titled "The Medicine Show," and recorded a comedy release in 1931, Emmett Miller’s last commercial recordings were made in 1936, on the Bluebird label, a subsidiary of Victor. These recordings were new versions of "Anytime," "I Ain’t Got Nobody," "Right Or Wrong," and a comic routine "The Gypsy." This latest version of "Anytime" inspired Eddy Arnold to cut it and it became the biggest hit of 1948. Emmett showed a lot more life on this new version of "Right Or Wrong," and it prompted Milton Brown & His Musical Brownies to cut the song in 1936, just six weeks before Milton’s death in a car accident. A month later, Bob Wills cut the song, and it’s become a Western Swing standard, also recorded by Merle Haggard in the 70's, and George Strait took it to the top of the charts in the 80s. Minstrelsy had become a dead art form by 1929, replaced by newer more refined sounds, and the final nail in it’s coffin was the advent of the movies. A great many of Minstrelsy’s performers had successfully moved over into the ‘hillbilly’ music genre. Music was becoming more refined. As an article in a Billboard magazine from the day stated, "Real hillbillies rarely have good nightclub acts." Just as white performers had once donned blackface to portray ‘Negroes,’ by the early days of country music marketing, ‘hillbilly’ music became another form of Minstrelsy, a masquerade of dress, manner, rusticity, and folksy backwoods caricatures that were portrayed by urbane performers. Even Jimmie Rodgers himself was very sophisticated and urbane beneath his folksy persona. It spread from there to the singing cowboys, visions of an imagined West fueled by Hollywood movies. While others like Jimmie Rodgers and Bob Wills easily made the move over to country music and became stars, why did Emmett Miller disappear into the world of the unknown? It appears for three main reasons. Emmett clung to Minstrelsy, even though he didn’t come to the art form until it’s dying breath and refused to give it up. In the decades that followed, he’d occasionally show up making a recording of blackface routines, despite the fact it had long ceased to be socially acceptable. The next reason is that his label had tried and failed to put him into the crooner mold, something that fell flat because Emmett’s whole style relied on his animated and wild vocals. Which is also the third reason why he couldn’t make the transition to country music. By the 1930's the record companies were looking for a smoother, less raw and rustic sound for commercial viability, and again, Emmett’s style was too untamed for even the ‘hillbilly’ sound. Emmett Miller was a voice that was recorded which was unlike anything ever recorded before or since, a combination of black/white and hillbilly/jazz. Though his career was short and he never gained commercial success, Emmett Miller, with his ‘trick voice’ and genre transcending music, provides the missing link in the transformation of what was a hodgepodge of the popular music sounds of the times and what would go on to become country music. Though Emmett has long been an overlooked footnote in music history, he is in reality one of the first greatest influences on the county music genre. In 1996, Sony/Legacy unearthed, gathered together and digitally mastered 20 Emmett Miller songs and packaged them with an in depth look at Emmett Miller and his legacy, that includes extensive liner notes and rare photos, titled Emmett Miller Minstrel Man From Georgia. For further glimpses into Emmett Miller, a closer look into the background of Minstrelsy, the history of the songs and his connections to and influence on the early country music stars, recommended reading is the book "Where Dead Voices Gather," by author Nick Tosches, the fruits of 20 years of research into the mystery of the elusive Emmett Miller. AnnMarie Harrington Take Country Back April 2003 |